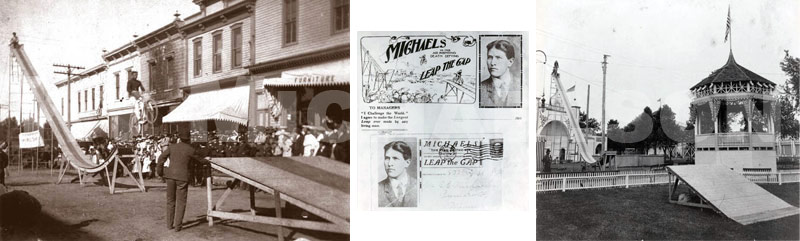

In 1905, my Great uncle, John Michaelson came up with a unique way of putting himself through college. Back in those days, there were obviously no Evel Knievel’s around, so what John concocted was nothing short of spectacular for that era. He built himself a 75-foot high, 200-foot long portable ski jump, and traveled with it throughout the Midwest. You may be asking what he would possibly do with such a ski jump, so I’ll tell you. Back then, not only were there no “Evel’s” around, but there were hardly any motorcycles either, and none of the handful of riders was anywhere near crazy enough to jump over anything. They had a hard enough time keeping the very unstable cycles under control just driving down the bumpy dirt roads, let alone anything else. John came from a different breed, though, and wanted to live on the edge of life, so he used his portable ski jump as a take-off ramp for his highly modified bicycle. I say highly modified because the difference between a motorcycle and a bicycle was very slim at a time when such a contraption was really just formulating. He would climb to the top of the ramp, and then use a rope to hoist his bicycle up to him. He had an assistant, who would hold the rear wheel as he mounted the bike. On the bottom of the ramp, there was a carnival barker who would collect money as he worked the crowd into a frenzy, telling them “the Great Michaels was Anton’s brother, John, was the first dare devil of many to come, including myself, and here’s about to lose his life if he did not successfully make the jump.” (John called himself the “Great Michaels” because he was afraid his Mother would find out he was risking his life to put himself through Hamline College.) He performed this daring stunt during the summer months at Wonderland Park on Lake Street in south Minneapolis on almost a weekly basis. His billboard read, “See the Great Michaels in his all inspiring, death-defying leap across the gap.” Before John made his jump, he’d shout out, “I challenge the world and agree to make the longest leap ever made by any living man.” Finally, after there was no more money to be collected, the brass band would start playing, and John’s assistant would let go of the wheel. John and the flimsy bike would scream down the ramp, jump over a picket fence, and land on a receiving ramp, setting the jump record of 53 feet.

He did this for a number of years, until he had an accident working with a new carnival called the “Gaskills Show.” The jump ramp was poorly lit up for the night show in Rochester, Minnesota, and as he left the steep incline, he almost went off the side of it. He lost control of the bike as he landed sideways, and the bike flipped over breaking his collarbone and his right forearm. Because of his injuries, they hired a new 27-year-old performer by the name of George Jackson to take his place. As they said back then, and still do today, “The show must go on,” so they made John the General Manager of the Gaskills Show. George made a number of successful jumps that season, until he performed on the main street in Zumbrota at the town’s yearly “Covered Bridge Festival.” George was sitting on the bike on top of the jump ramp with his helper holding the rear wheel, when a local mortician stepped out of his place of business. George called down to him from his place on top of the ramp, and said, “Do you want to measure me before I jump?”

“I don’t measure live men,” was his reply.

An instant later, his helper prematurely let go of the wheel, and the bike toppled off the side of the ramp, crashing head first into the ground. The crowd was horrified at the sight of this young dare devil sprawled out on the ground in front of them, in severe agony. His neck had been broken, and he succumbed to his injuries a short time later. John ended up leaving the carnival to go into business with his two other brothers, Joe and Walter. I guess the old mortician got to take his measurements after all.